I hope our Flemish readers will forgive our boldness in using one of their very own terms to name one of our products. Well, at least it is a neat and classic pair of cycling bib shorts, very flandrien indeed, all black with a small white Siroko logo. But first, let’s see what a flandrien or flandrienne actually is so that we can apologize to the people of Flanders.

The first to use the term flandrien when referring to a cyclist was the sports journalist Karel Van Wijnendaele (real name Carolus Ludovicus Steyaert). He did so at the beginning of the 20th century, first in local chronicles, and later in a newspaper called Sportwereld. For Van Wijnendaele, a flandrien was an attacking cyclist, physically powerful, showing unwavering perseverance and mental endurance. Carolus’ harsh childhood serving wealthy French-speaking families to afford food, shaped his outlook on the flandrien cyclists’ character. As he wrote in 1942: “The mastery of the Flandrien over the French stemmed from the fact that they were the children of people who had to toil and slave to survive. […] That’s why we’d never give up. […] If things in life are too easy for children, they cannot be raised sparingly or rigorously enough!”

French-speaking reporters, on the other hand, did not share his opinion of the flandriens. They described them as savages because of their aggressive and foul behavior when competing. They were probably heavily influenced by the bad reputation of the flandrien seasonal workers who traveled from East and West Flanders in the early 20th century to work in Wallonia and northern France. This detail is crucial. Back then, a flandrien was not simply a person born in Flanders. A flandrien was a Fleming born in East or West Flanders, two of the five provinces that make up today’s Flemish region, but historically the central core of the former County of Flanders.

The historical context also plays an important role. We are at the dawn of the Great War, when symbols, cultures and nations are being glorified… Therefore, those who for the French-speakers were savages, for Karel Van Wijnendaele were heroes, the embodiment of the Flemish people: poor, but strong and with an unbreakable willpower.

At the same time, cycling was booming, not only as a popular means of transport, but also as a way of making a living thanks to cycling races. For many young flandrien, destined to a life of hard work, it was a chance to escape. One of them was Cyrille van Hauwaert. Born in Moorslede (West Flanders) he came second in the 1907 Paris-Roubaix and two weeks later won the Bordeaux-Paris. The following year he won Milan-San Remo and conquered the Hell of the North. Rich and famous, he became an idol and a role model for many of his fellow countrymen. However, at that time, aspiring cyclists had to leave Flanders to compete because the Flemish region was not yet the hotbed of bike racing as we know it today.

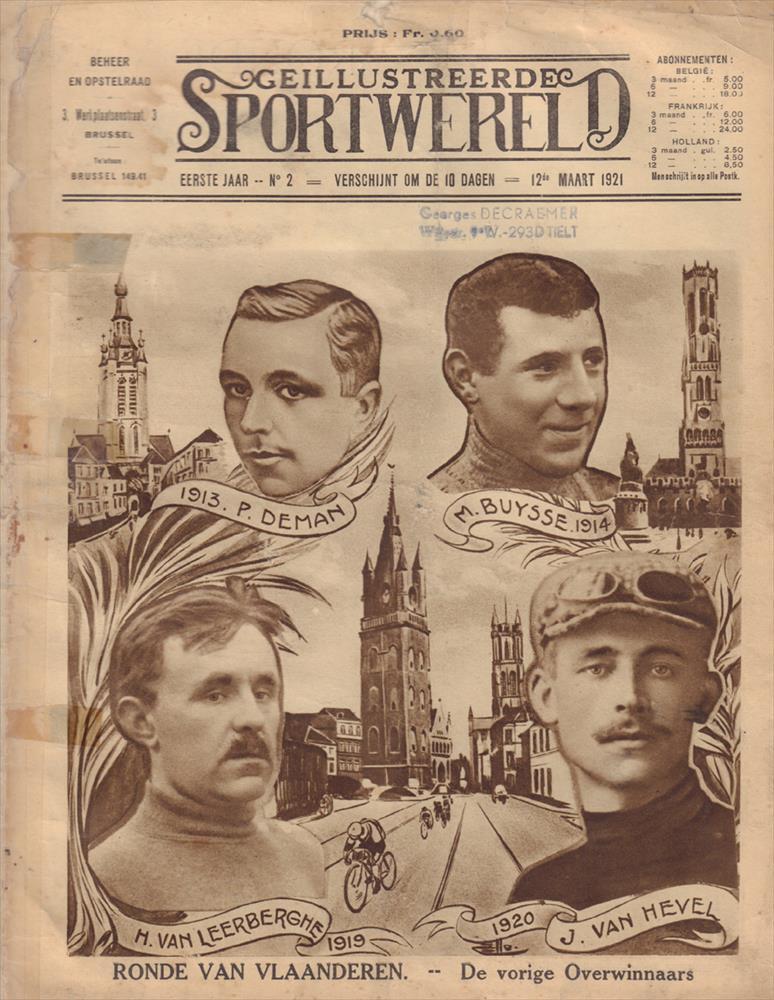

This was partly solved by the first Tour of Belgium (Baloise Belgium Tour) held in 1908 and, above all, by the first Championship of Flanders (Kampioenschap van Vlaanderen or Koolskamp Koerse) also held in 1908. It is no coincidence that on the same day that the 1912 edition of this purely Flemish race was held, the first edition of the Sportwereld – in which Van Wijnendaele worked – was published. It happened a few months after Odile Defraye, a pure flandrien born in Roeselare (West Flanders), won the Tour de France. This became the driving force behind the first Tour of Flanders, held in 1913 and organized by the Sportwereld newspaper, with Leon Van den Haute at the helm. The aim, apart from selling newspapers, was to spread and exalt the Flemish pride.

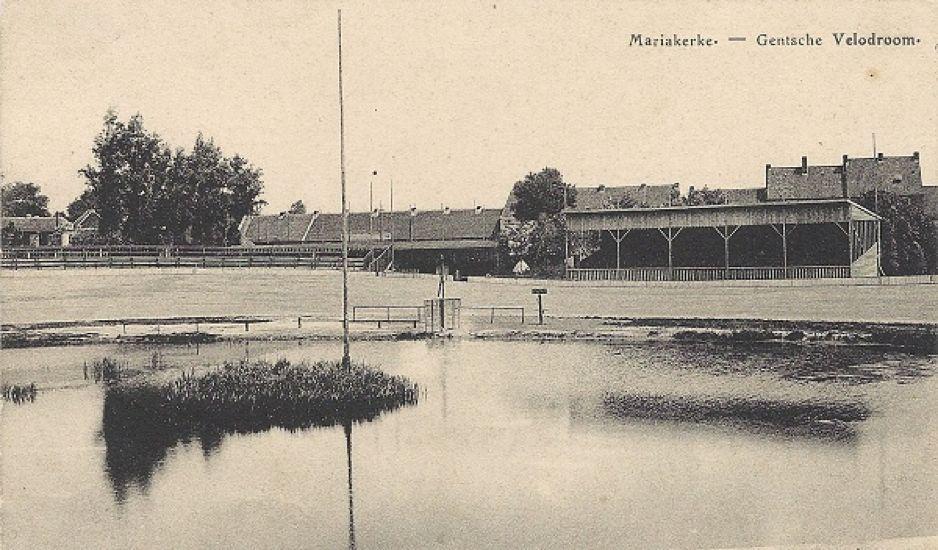

324 kilometers starting in Ghent and finishing at the Mariakerke velodrome, passing through St. Nicholas, Aalst, Oudenaarde, Kortrijk, Veurne, Ostend, Roeselare… all without leaving East and West Flanders, and without the cobbled climbs that are now a hallmark of the race. The winner was flandrien Paul Deman whose life story beyond his cycling career would make for a spy movie.

The turnout was low and so was the level of the competition. Although Deman was riding with the French Automoto team, Van Wijnendaele accused the French teams of banning their Belgian riders from the race. The fact is that great Belgian cyclists of that time, such as Marcel Buysse, who had just finished third in the Tour de France winning six stages with the French team Alcyon-Soly, or the aforementioned Defraye and van Hauwaert, did not participate in the first edition.

The following year, Marcel Buysse did not listen to his team’s directions and won the second edition. Seeing how their great idols not only won in France, but also at home, was a major boost for the flandriens and the Flemish pride. Then, five hard and cruel years had to pass for the cyclists to compete again. After the end of the Great War, the Tour of Flanders never stopped, not even during World War II. It has undergone many changes, difficulties and controversies along the way, until it became what it is today: the most important international sporting event of the year in Belgium and especially in Flanders (in 2014 the broadcast of the race reached a market share of 71% in Flanders).

While some competitions already existed before, the racing scene as we know it today has gradually developed. From the small local races to the great classics and semi-classics, including the packed cyclocross race calendar. And apart from that, a myriad of local groups, fan clubs, professional teams… Cycling became the sport of the Flemish people. Mainly because the flandriens stood out and won from the very beginning, which made for great content and sold newspapers such as the Sportwereld or the Het Nieuwsblad, becoming a talking point on the streets and in workplaces.

If we look back at the history of the great cycling competitions we would find Flemish names like Lucien Buysse, Marcel Kint, Jef Scherens, Briek Schotte, Fred De Bruyne, Rik I (Rik Van Steenbergen), Rik II (Rik van Looy, The Emperor of Herentals), Roger De Vlaeminck, Freddy Maertens, Lucien Van Impe, Eddy Merckx, Johan Museeuw…. we could keep going, adding many more names until today, but these cyclists alone explain why cycling is more than just a sport in Flanders.

Cycling is part of the Flemish culture, for many it is almost a religion, with everything that it entails. But it has also become a business that needs to be promoted internationally in order to bring profits. It could not be otherwise in one of the most prosperous regions in Europe. This creates tension between the orthodox and the unorthodox on issues where sport and culture are intertwined, such as the discrepancies in the use of the concept in question. The term flandrien was first used only for cyclists born in East or West Flanders, then for all Flemish cyclists, then for any cyclist born in Belgium, and when the Flandrien Of The Year award was created in 2003, people actually chose an Italian cyclist Paolo Bettini. If Karel Van Wijnendaele had been alive, his column in Het Nieuwsblad would surely have raised more controversy than the one written by Patrick Lefevere today.

Perhaps Carolus thought that his countrymen were superior human beings and that no cyclist outside of Flanders would have the features of a true flandrien. He was wrong. Cycling is full of fighters. Cyclists from all over the world who, whatever the conditions and circumstances, do not give up, attack, use unbelievable amounts of power and have as much mental stamina as physical endurance. Flemish people who love cycling beyond nationalities are well aware of this. The widespread use of the term flandrien to define cyclists such as Bettini or Cancellara, is not an offense to them, but quite the contrary. It extols and elevates the flandrien spirit. That’s why cyclists from all over the world will never stop traveling to Flanders, trying to work their way into pro cycling. Just as a young American rider did in the early 1980s to prove that, in addition to having a spectacular “engine”, he was also tenacious. Three years later he became the first non-European World Champion and in 1986 he did the same by winning his first Tour de France. You’ve heard of him, it’s Greg LeMond.

Now, let’s go one step further. The cycling world is full of fighters, so any cyclist can be a flandrienne or a flandrien. The one who gets on the bike after finishing their workday and does an interval workout, knowing that they have to get up early the next day and go to work. The one who has decided to get in shape and starts pedaling, feeling like his heart is about to explode on every climb, but doesn’t give up and in a few weeks is already able to do the same climb and talk at the same time. Anyone who’s up for the challenge. And if that’s not enough and you want to become even more flandrien, here’s the Flandrien Challenge. Ride the 59 segments with the most famous berg and cobble sections of Flanders in 72 hours and your name will be engraved in stone in the hall of fame of the Tour of Flanders Center (Centrum Ronde van Vlaanderen). We don’t know what Van Wijnendaele would say, but don’t let the bib shorts stop you from becoming a real flandrien or flandrienne.