We have already told you about the health benefits of cycling in a previous post. While this correlation appears in study after study, let’s not forget that correlation does not imply causation. In other words: you can go out cycling, feel good while pedaling, as well as for a while before and after training, but some problems are still there, and sometimes, no matter how much we pedal, they end up taking their toll on us.

That’s why we are going to talk about the relationship between cycling and mental health in this post, using some examples of professional cyclists whose stories, although some of them had tragic endings, help us talk about anxiety, depression, eating disorders and drug abuse.

But first, we would like to stress that we are not experts in the field and we are only sharing information to reflect on a huge health problem worth paying attention to. Two facts to help us realize that without mental health there is no health: the WHO considers that in 2030 depression will be the leading cause of morbidity worldwide and the use of medications to treat mental health problems has been on the rise for a decade.

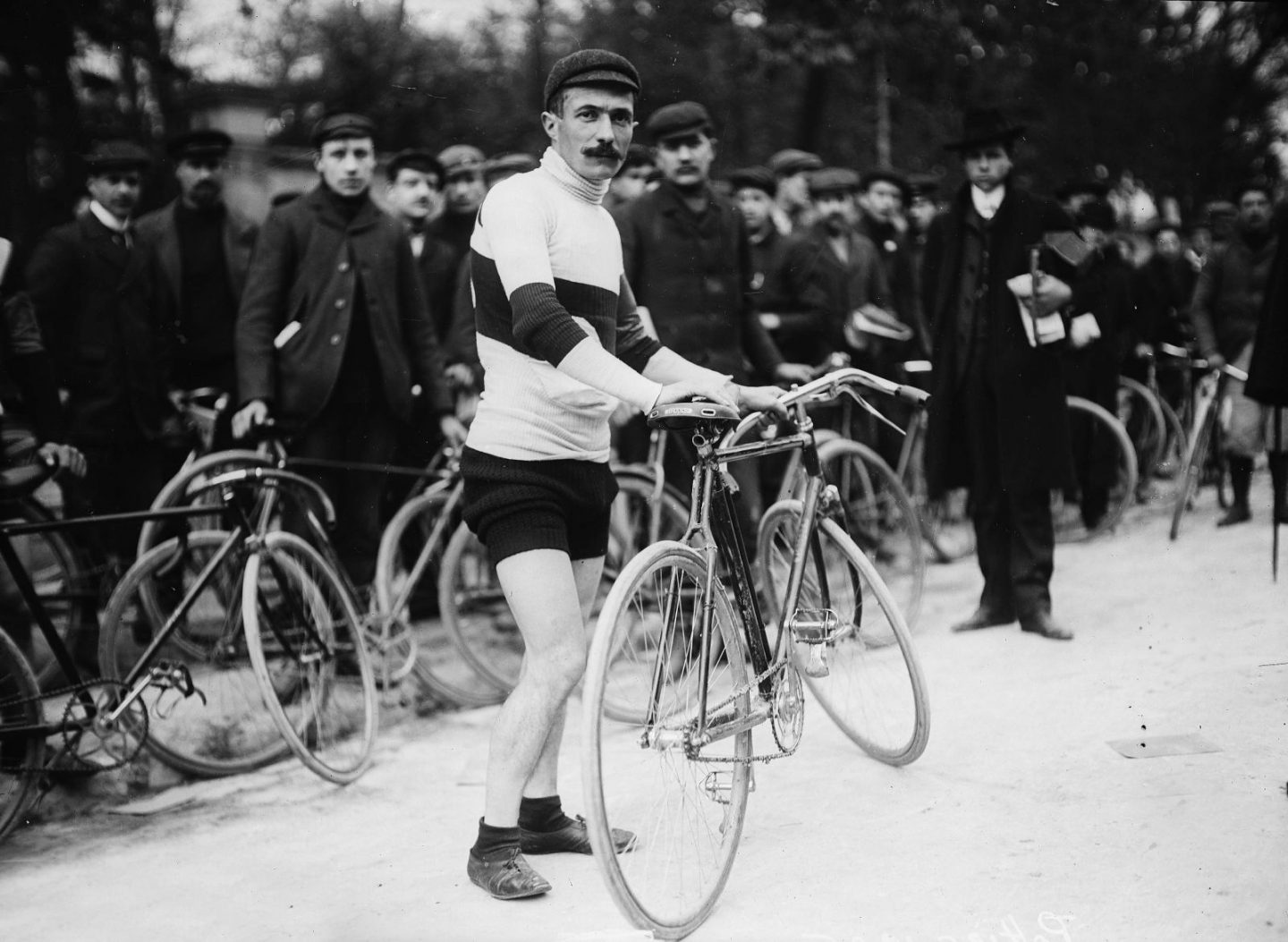

René Pottier

The case of the 1906 Tour de France winner illustrates something that keeps happening: The lack of understanding of mental health problems and suffering alone and in silence. Nobody was able to comprehend the Frenchman’s suicide 6 months after winning the Tour with overwhelming superiority. The press at the time said that René was “unlucky in love”. Allegedly, his wife had had an affair while he was racing the Tour, but it is clear that René Pottier was suffering from a “deep malaise that nothing, not even glory, could overcome”.

What was tormenting René Pottier? Mental health problems do not usually have one single cause but rather a combination of factors: genetics, social environment, traumatic experiences, stress, drug use, alcohol, unfulfilled expectations… Therefore, anyone can suffer from a mental health problem. That is why it is necessary to seek or ask for help at the first signs. Do not suffer silently in solitude. Seek specialized medical assistance, as well as support groups. There are specialized sports psychologists to help athletes in life and in competition. Even so, we keep witnessing tragic cases such as the story of the young American cyclist Kelly Catlin.

Tom Dumoulin

When the Dutch cyclist announced on January 23rd, 2021 that he was withdrawing from competition, it took everyone by surprise, but something has changed in the sports industry over the past few years. The upside is that the athlete clearly voiced his problem and received the support of his teammates and the team. The downside is that some people still find it hard to understand (one of the questions Dumoulin was asked seems to be about that) because they only see the privileges of an elite athlete but not the pressure, the expectation to perform and justify his salary, the social networks, the media, sponsors…

Tom has returned to racing in 2021, but other cyclists and the rest of us should take his example not as an exception due to his privileged professional situation but as what should be the norm. When someone breaks a leg no one holds it against them and everyone gets it. Why isn’t the same true for a mental health problem? An ex-pro Phil Gaimon explains it very well: “The only thing that’s crazy is how long people wait to take care of themselves […] You wouldn’t walk around with a broken arm and you shouldn’t ignore your brain, either”.

There are more cyclists like Dumoulin. Spaniard Javi Moreno also quit and came back, successful German sprinter Marcel Kittel retired stating that “cycling is beautiful but professional sport is another story” and young Frenchman Theo Nonnez announced in April 2021 that he was quitting cycling.

Jenny Rissveds

The Swedish female mountain biker won the Olympic title in Rio de Janeiro in 2016 at the age of 21. A few months later, in 2017, Jenny Rissveds withdrew from mountain biking, social media and the world to focus on her mental health. In this Instagram post she explained that in addition to depression, she had been diagnosed with an eating disorder: “The only thing that circulated in my head was to eat as much as possible and then figure out how to get to the toilet. My life started to look like an addict’s and I probably became an addict myself. […] Somehow I knew my obsession with food and my body was connected to my depression and that one meeting at the psychiatric department at the hospital became my wake up call”.

The weight obsession affects cyclists at all levels. The problem is that cycling requires a lot of energy. You have to eat but you can’t get “fat”. As a result, despite all the advice and help that professional athletes receive, there are cases of eating disorders in the peloton. Ben King and Janez Brajkovič suffered from bulimia, and Rohan Dennis claimed that to lose weight he came close to an eating disorder. The price Catherine Marsal had to pay for her top performance was osteoporosis.

There is a fine line between reaching the optimal weight to perform at our best and wanting to weigh less and less, thinking that this will improve our results. These examples prove that if an elite athlete working with dieticians, nutritionists and trainers can suffer from eating disorders, then anyone can suffer from them, putting their health at risk. Jenny Rissveds was able to stop and find the will to enjoy life, food, cycling and competition again.

Frank Vandenbroucke

It would be hypocritical of us not to mention drug use related to mental health problems in cycling. There are plenty of examples. From lesser-known cyclists such as Jesús Manzano or Mauro Santambrogio, to world-famous riders including Bjarne Riis or Marco Pantani, all of them involved in doping scandals similar to that of Frank Vandenbroucke. However, just as many people take all kinds of drugs without showing mental health problems, many cyclists have also used doping without suffering such consequences. This means that there must be something else: the combination of factors that we mentioned earlier.

The Belgian rider had a complicated childhood full of family problems. He became a pro at the age of 19 in a peloton where doping was rampant and Vandenbroucke became addicted to all kinds of substances. This is how he described it in his biography: “To Stilnoct (a sleeping drug) and amphetamines, I added Valium… Sometimes I didn’t sleep a second in five days. I started seeing things, people who didn’t exist. I used to hear them coming. They were coming to arrest me.” They were indeed. In 2002 Belgian authorities searched his home and found EPO, clenbuterol and morphine. The mix of drugs, chaotic life and personal problems led to a suicide attempt in 2007 and his death in 2009 at the age of 34.

Substance abuse, alcohol and drugs are fuel to ignite physical and mental health problems. A wholesome, calm lifestyle and a healthy diet, regular exercise, avoiding stress and the use of toxic substances, helps prevent mental health problems.

Cyclist’s retirement

Finally, there is something fundamental for a professional cyclist, as well as for any person who finishes his or her working life.

Retirement can be tough for athletes if they are not well prepared. There is not as much data on cycling, but let’s take a look at other sports: 40% of Premier League football players and 60% of NBA players go bankrupt within 5 years of retirement. In the NFL 78% of players have financial problems within two years of retirement. These statistics show sports with much more money than cycling. Therefore, cyclists should not put all their eggs in one basket. They should prepare for retirement as it often means financial, personal and emotional loss.

It’s crucial to manage sports careers and retirement by planning ahead. Work on what you think, what you feel and what you do to find your own path for the future, not the path that others have set for you. Many cyclists continue to pedal because they love cycling. Some continue to be involved in cycling in one way or another, but there are also cyclists such as Australia’s Anna Meares who retire suddenly and involuntarily, suffer different kinds of problems, and need time and help to adapt.

The examples of cyclists we have provided in this article are just the tip of the iceberg because mental health problems among athletes are as common as in the population at large. We may think they are privileged, real superwomen and supermen, but at the end of the day they are only human.